During my travels, I’ve been fortunate to see and experience much that is worth sharing.

My hope is that these images touch your hearts, much as the USA’s natural beauty has touched mine.

May the adventurous among you benefit from the travel information I share on these pages!

I had the good fortune to live in Montana’s Gallatin Valley from 2009 to 2010. I had visited the area several times prior to moving there, and mountain life has always been my “comfort zone.”

Of course, the Valley was not called the “Gallatin” by those who came before us. Instead, the native Americans called it the “Valley of the Flowers”, and that is how I will always remember it. Early June is when spring begins in the foothills of the northern Rockies, and with spring comes the beginning of wildflower season.

To see what the Custer Gallatin National Forest has to offer, it’ helpful to visit the forest’s website. One has to get off Interstate 90 and onto some side roads, bumpy Forest Service access roads, or the large network of biking / hiking trails. The latter option is the most rewarding one. Hiking a trail gives one’s mind a rest, and absorbing the fresh mountain air is also healthy!

From the vantage point of what was once my back yard outside of Bozeman, the Bridger Mountains rise in the east, as large as life. They were, in fact, so close that I could get to the Truman Gulch trailhead in 15 minutes. Indeed, the Truman trail became my regular exercise regimen after returning home from work, both winter and summer.

As is the case with many a trail, the really nice scenery at Truman Gulch begins to appear after one has gained enough altitude. Until then, it’s hard to see the forest for the trees.

An unusual feature of the Truman Gulch trailhead is that its winter parking lot adjoins a sloping meadow which looks northeast over a wide green valley. The meadow is generously decorated with Indian paintbrush in midsummer, and one can see straight across the valley to Ross Peak in the Bridger Range.

Those who keep to the trail long enough can get to a pass over the Bridgers, on the south side of Ross Peak, then continue down the Ross Pass Trail to Bridger Canyon on the east side of the mountain. Most folks who want to get to the canyon, though, simply follow the mountains south till they reach Highway 68, a state highway which leads north to Bridger Canyon and the Bridger Bowl ski area.

Highway 86 is the road I found myself on not long afterward, on June 9. Though the peaks of the Bridgers were still topped with snow, I hoped to find some early season wildflowers along the Ross Pass trail—but that day, it was what I saw right off the main highway that blew me out of the water.

Just after passing the Bridger Bowl access road and topping the Bridger Divide, I had to pull over onto the east shoulder of the highway. A large pasture, rising gently up the west flank of Grassy Mountain, was carpeted with tiny purple shooting stars! Shooting stars, ordinarily, are seen in smaller groupings, where there’s lots of sun and moisture, often near waterfalls like Champagne Falls on Hyalite Creek. I felt like a kid who, having only ever seen a giraffe or two at the zoo, is suddenly dropped into an entire herd of the creatures on the African savanna.

The pasture was privately owned, but fortunately I located the owner and was given the green light to roam the flower-filled hillside to my heart’s content. I captured the field from nearly every possible vantage point. After returning from my trip, I decided the nicest angle was one facing downhill, looking northwest across Bridger Canyon to Ross Peak, the view in the picture displayed here.

Shooting stars, as I mentioned, are small things. The only practical way to get my camera close enough to ground level was to plop my rear unceremoniously onto the ground. I was a little annoyed, at first, that my pants got wet no matter where I chose to sit, but I let it pass. Soggy pants are hardly the worst thing a photographer has faced in the field!

After living in the Rockies for a while, I finally learned that mountains really aren’t made of solid chunks of rock; they are, in fact, like sponges, absorbing moisture in the winter and spring. Gravity pulls at the water inside the big rocky sponges, and it eventually finds its way out of the rock via the path of least resistance.

In this case, the pasture facing Highway 86 was an enormous “spring seep” fed by snowmelt from Grassy Mountain to the east, out of my field of view. In any case, I have never seen shooting stars in such abundance since that time... so it’s my pleasure to be able to share with you what the folks living near Montana’s Bridger Divide take for granted every spring!

↑ RETURN TO MAIN MENU AT TOP OF PAGE ↑

At 692 miles, the Yellowstone River is—happily—the longest un-dammed river in the United States. In 2009 and 2010, I lived in the Rockies, close to the headwaters of the Yellowstone, which spring mainly from the snows covering the Absaroka Mountains in Wyoming and Montana.

After the channel of the Yellowstone reaches north to Livingston, Montana, it bends eastward and begins collecting water from its major tributaries, which also spring from cold, clear mountain creeks. The first of these is the Boulder River, which flows north from a canyon which divides the Absaroka and Beartooth mountain ranges. The headwaters of the Boulder are in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness. Like most national wilderness areas, access is restricted to non-mechanized travel.

Fortunately, the lower portion of the headwaters lies outside of the restricted access wilderness—and one can get there from Interstate 90 in an hour. The upper Boulder valley is overshadowed by Monument Peak and Sheepherder Peak, which are pictured below. This photo was taken in mid-June, just after the snow had melted from the open meadow. Perennial pasqueflowers, quick to feel the warmth of the sun, were already in bloom. Usually, by July, folks with an ATV or a small, sturdy 4WD can get to this place from Interstate 90 by taking exit 367 at Big Timber and traveling south on Montana Hwy. 298. At the boundary of the Custer Gallatin National Forest, the pavement ends; travelers can continue south on Forest Service Road 6639.

Panoramic view of Monument Peak and Sheepherder Peak, Absaroka Mountains — Click / tap image to view full size

Summer travelers can enjoy fly-fishing, kayaking, camping, and hiking in this valley just as much as in the Yellowstone valley just south and west of the Boulder River, if not more; in this part of Montana, visitors are few and traffic is light. Such were my thoughts as I drove through the valley in June of 2009. As I passed the Box Canyon Pullout parking area shown here, I absently wondered why people with 4WD pickups were unloading their ATVs at that spot instead of continuing farther south on FS 6639. I learned why soon enough!

Back in 2009, Google Earth satellite imagery was low-resolution, and both my Forest Service road map and Google Maps assured me FS 6639 contined south another five miles. But in the current view of Box Canyon Pullout, you’ll notice the road all but disappears south of the parking area I just mentioned. And that is exactly what I discovered on the ground during my journey. I stopped my SUV and walked south a bit. The graded gravel road had ended at the parking lot behind me. All that remained of the road was a rocky, primitive 2-track trail, and it was now obvious why the other guys were leaving their larger rides at the parking lot.

Unfortunately, I didn’t own a horse or ATV. My eyes bored into the rocky trail ahead, until I finally decided I would chance it with my SUV. I was unwilling to walk five miles just to get to the wilderness boundary, when I knew yet another hike would await me inside the boundary!

Besides, there’s little scenery visible on that five mile route. Once one gets south of the confluence of the East Fork of the Boulder River, the valley narrows into a canyon, and it becomes hard to see the forest for the trees, as the saying goes.

Whitewater on the upper Boulder River

In any case, my mind was far away from the scenery. I got out of my car many times, but only to figure out exactly how I’d have to align my front tires to keep from bottoming out on an unyielding chunk of granite. I also had to ford the Boulder a couple of times. In that area, it’s merely a creek instead of a river, so that part felt fun... kind of like Jeep’s TV commercials.

After what seemed an eternity of stop-and-start driving, I finally reached the five mile mark, just south of where Basin Creek and Sheep Creek empty into the Boulder. At that point, one can follow the road roughly westward along the Basin Creek drainage to the site of the Independence Mine.

Exploring abandoned mines is something many hikers and ATVers in the Rockies like to do. If the route had not been buried in snow, I would have done some exploring myself; but I had arrived at the Boulder headwaters about a month too soon for such a journey. The access road follows the north side of Independence Peak, and usually doesn’t melt out till sometime in July.

I observed that an unmarked and unnamed two-track road forked south where FS 6639 turns away from the Boulder River canyon. Following the mystery trail, I pleased to discover that it was much less gnarly than the Forest Service road. I followed it about a quarter of a mile to a place where the canyon opens up to an expansive meadow under the shadow of Monument Peak. The snow had only recently melted off the lower meadows, which were blanketed with pale yellow pasqueflowers.

I took quite a few photos at this spot, including the wide panorama at the top of this post. Midday light is generally not the best for capturing photos of wildflowers and mountains, but it worked well for me that day.

If I had wished to “get away from it all”, I couldn’t have picked a better spot than this one. There wasn’t another human being in sight. The air was crisp and clear, and I could hear nothing except the trickling of melted snow, the breeze in the spruce trees, and a few bird calls. It was the perfect spot for a lunch break.

I had reached the northern boundary of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, but I opted out of hiking into it. The snow had not yet melted beyond the open meadow, and I didn’t have a pair of snowshoes with me. I figured I’d rather explore the lower reaches of the Boulder River, having noticed many photo ops on my way upriver.

I returned from the Absaroka Mountains the way I had come, at a more leisurely pace. I don’t recall seeing any ATVers until I passed the parking area once again, which wasn’t surprising; they probably already knew that the road I had chosen would be a dead end for motorized travel until the snow melted off Independence Peak.

The graveled Forest Service road crosses the river over four bridges. At that time of year, the Montana Rockies are nearing the end of the spring runoff, and fording the Boulder River downstream is impossible. The riverbed is full of large granite boulders, and the whitewater rapids pictured here are can sweep a Jeep downstream during spring runoff. The Boulder definitely belongs to the “wild and scenic river” club.

Continuing downstream, the mountains give way to limestone foothills. The valley begins to widen, and one passes many Forest Service trailheads and campsites—ideal for those who want to “get away from it all”, but (if you’re like me) lack the endurance to hike for miles into the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness.

The most accessible scenic location in the Boulder River valley is Natural Bridge Falls Picnic Area, a Forest Service day-use area located just within the National Forest boundary, 25 miles southwest of Big Timber on MT Hwy. 298. It’s a great day-trip or family trip destination with a good network of trails, including one which is handicap-accessible.

Montana’s Custer Gallatin National Forest has plenty of waterfalls. Few of them are large, but many are picturesque and well worth visiting. In early summer, Natural Bridge Falls is both large and picturesque. If you click or tap on the photo shown here to get the full panoramic view, you’ll know what I mean.

In ages past, a short way upstream of the picnic area, the churning waters of the Boulder tunneled underground through the relatively soft limestone riverbed. The subterranean channels are now so large that the river runs underground for much of the year, re-emerging from a round opening in the limestone cliffs at Natural Bridge Falls.

As the river swells during spring runoff, it overfills the underground channel and flows over the surface riverbed—then makes a dramatic 105-foot plunge just above the lower falls, as seen in this picture. To spice things up just a bit more, there is a small “spout” of water jetting out of the rock between the upper and lower falls.

The pool below the falls is shallow, which makes for a lot of churning, foaming, spray, and mist—perfect ingredients for a rainbow, if one happens to be viewing the falls from the west side of the gorge late in the morning, as I did when this image was captured.

Some time ago, a client gifted a print of this image to a relative who once lived in this part of Montana. Shortly afterward, she sent me this message: “Just wanted to let you know that my father-in-law loved the photo. He said he can smell the pines and feel the crispness of the air, it takes him right there. Thank you again!”

When I receive feedback like that, I’m grateful for the reminder of why I share these experiences on “Jerry’s Journeys”!

I highly recommend a visit to the Boulder River valley for anyone who happens to be traveling central Montana via Interstate 90... anyone who wants to “get away from it all” for a little while, as I did many a time.

↑ RETURN TO MAIN MENU AT TOP OF PAGE ↑

Visitors to southern Montana, traveling westward via Interstate 90, get their first sight of the Rocky Mountains while driving over the foothills of the Beartooth Range, which extends south into Wyoming. As one travels farther west, the Interstate roughly follows the south bank of the Yellowstone River. Approaching the town of Big Timber, one can see a small but high mountain range off to the north, as well as a small green sign alongside the highway which reads “Crazy Mountains”. During summer trips to the Rockies, when our family passed that sign, I could never pass up the opportunity to tell a bad joke about it, usually something like “The Crazy Mountains: You’d have to be crazy to go there!” Although that is obviously not true, it is true that most visitors—eager to see the Yellowstone area to the south—rarely detour northward at Big Timber to investigate the Crazy Mountains.

Panoramic view of the Crazy Mountains, captured shortly before sunset in midsummer — Click / tap image to view full size

To make amends for those bad jokes of years past, I decided to share the highlights of the Crazies in this post. These are things I learned while exploring the highways and back roads between Bozeman, Livingston, and Big Timber.

The Yellowstone District of the Custer Gallatin National Forest includes much of this area. The Gallatin Range stretches northward from the boundary of Yellowstone National Park to Bozeman Pass. Continuing north from the pass on gravel Forest Service roads, one can explore the Bangtail Mountains. The Bangtails are a small range—lacking major streams and lakes—but they also lack restrictions on motorized traffic, making them a favored weekend destination for many local campers and hikers. And they also offer great views of the Crazy Mountains and the Shields River valley. While exploring the Bangtails one summer evening in June, I was lucky enough find one such viewpoint and capture the pre-sunset panorama of the Crazy Mountains displayed above.

On subsequent visits to the Crazies, I ventured farther from Bozeman, traveling up US Hwy. 89 from Livingston to the Shields River Road, which leads eastward to several Forest Service spur roads, as well as motorized and non-motorized mountain trails. Most of the trails to the alpine lakes at the base of the high peaks in the Crazy Mountains are non-motorized, but are popular hiking and horseback routes.

My favorite part of the Crazy Mountains is the waterfall zone of Big Timber Creek, which is accessed from Interstate 90 from Big Timber north via US Hwy. 191 to Big Timber Canyon Road. It’s a great destination for a day trip; though the Forest Service access road makes for a long and rough drive to the Big Timber Creek trailhead and Halfmoon Campground, once you arrive you’ll find the hike to the waterfall short and pleasant.

Big Timber Creek Falls is actually a chain of waterfalls and smaller cascades that begins about a quarter mile upstream from Halfmoon Campground. The elevation of the creek drops about 350 feet in that section, creating a stretch of whitewater rapids which then plunge down more steeply into a series of pools. The traihead map linked above is centered on the steep drop into the largest pool, which is pictured here.

I returned to the falls a few weeks later with my son, who enjoyed exploring all the twists and turns of Big Timber Creek almost as much as I did. Nowadays, he has fonder memories of the campfire we made and the cheddarwurst and s’mores which followed our hike. At that time, he was still a teenager with a healthy appetite. After our climb, I was fairly hungry myself!

Some time later, I showed my son and a few of my friends some YouTube clips of Big Timber Creek, which had been shared by adventurers who’d kayaked down the quarter mile of whitewater at the height of the spring runoff. Some kayakers get a rush from the narrowness and steepness of the large drop pictured here. The less fortunate ones just get banged up. Before you can conquer the mountain, you gotta respect the mountain. As you may know already, I learned that by getting my own share of bumps and bruises... and I found out how easily that can happen without the aid of a kayak.

There are several images I captured at the creek which I liked enough to print. One of those is the photo of the shooting stars displayed here, with the waterfall slightly out of focus in the background. Shooting stars are small, brightly colored wildflowers that tend to flourish in places that are constantly damp—such as rocky, mossy ledges alongside waterfalls, or spring seeps as I mentioned in an earlier blog post.

Getting back to where I started this tale: Big Timber isn’t a place you’ll get to quickly, even though it’s located near Interstate 90... but if you do find yourself in that part of the country with a day or two to spare, you’d be crazy not to visit the Crazy Mountains!

↑ RETURN TO MAIN MENU AT TOP OF PAGE ↑

Some years ago, I lived on the east side of the expansive Gallatin River valley in Montana. The Gallatin, Madison, and Jefferson Rivers join at Three Forks, the place where the Missouri River begins its journey northward. All three of the tributary rivers spring from smaller mountain streams in several ranges of the Rocky Mountains, so practically everyone who lives in the lowlands surrounding Three Forks has excellent views of at least two mountain ranges, and sometimes more.

The place where I lived is just northwest of Bozeman, so I had an excellent view of the Gallatin Range to the south, a couple of smaller ranges to the west—and to the east, practically in my back yard, I had a closeup view of the Bridger Range. Naturally, I spent most of my hiking time in the Bridgers, eventually settling into a routine of driving home from work (a 15-minute trip) and hiking in the foothills of the Bridgers before dinner (another 15-minute trip). Later on, when I lived in Denver and found that it takes the better part of an hour just to get out of town, I appreciated the convenience I’d enjoyed in my backyard mountain range in Montana!

A fringe benefit of my Bridger Mountain hikes was the timing, normally at the end of the day, when the deer and elk come down from the mountains to graze in the valley. At that time, there are also lots of interesting colors and patterns in the sky. To top it all off, I gained several hundred feet of elevation driving to the trailhead, allowing me a better view of the mountains across the Gallatin Valley.

For example, I had an outstanding view of the Spanish Peaks from the gravel road near a Forest Service trailhead one evening, which is pictured here. You’ll notice that the foothills in the center background drop down to form a gap. That gap is where the Gallatin River flows out of the mountains. It’s 22 miles from that spot to the northeast side of the valley, where I was standing, so the Spanish Peaks look small compared to the dissipating storm clouds hovering over the valley in this photo.

Due to my closeness to the Bridger Range, I didn’t hike as much in the Gallatin Range or the Spanish Peaks, but I made enough treks to get great views of the Spanish Peaks on a few occasions.

The author (as he looked in 2008) takes a much-needed break from climbing to view the Spanish Peaks.

During the first such trip, my destination was Hidden Lake in the Gallatin Range. There is a broad windswept ridge encircling Hidden Lake, on the west side. There is no trail up the steep slope from the lake to the ridge, but since the elevation gain was only 800 feet, I figured it was worth a try. After much climbing, puffing, and panting, I reached the top of the ridge, at an elevation of 9770 feet—high enough to get great views of the Gallatin Range. Looking east, I could see the Hidden Lakes chain—and all the way across the Gallatin Range to Windy Pass. Looking west, I was pleasantly surprised at the closeup view I had of the Spanish Peaks, which are visible in the “selfie” I’ve posted here.

The high peaks are part of the Lee Metcalf National Wilderness Area, which only permits non-mechanized access within its boundaries. Surrounding the wilderness is the Custer Gallatin National Forest and private land, which offer access to the Spanish Peaks via several trailheads and a few short, unpaved Forest Service roads. Many visitors from Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley are familiar with the Spanish Creek Road, which leads to the Spanish Creek trailhead just north of the wilderness boundary.

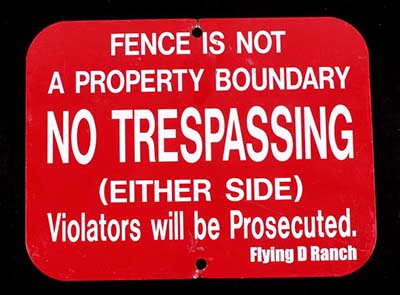

When you no longer see these signs every hundred yards of fenceline, you know you’re getting close to National Forest land.

The Spanish Creek access road is easily found on the west side of US Highway 191, where Spanish Creek empties into the Gallatin River. The access road more or less follows the creek upstream, and crosses Ted Turner’s well-known Flying D Ranch. Most ranchers have their land posted, but the Flying D has gone all out, making sure every hundred yards of fenceline is marked with the red signs pictured here. When I lived in Montana, it seemed like an amusing example of overkill; but considering the notoriety of Ted Turner and the popularity of the route, I understand the necessity of a well-marked fence. If you happen to visit the Spanish Peaks via this route, you’ll know you’re approaching National Forest land when the route turns south toward the mountains and you stop seeing the red signs everywhere.

The website at this link has a good interactive map of the Spanish Creek trailhead (indicated by the green marker on the map) and some helpful information about the trails which one can choose to hike.

I have yet to hike the South Fork trail all the way to Mirror Lake, but those who make the trek can expect to see something like this Google Maps view, or better, depending upon the weather and the time of day. I hiked the Spanish Creek trail, but didn’t arrive at the trailhead till late morning. I realized that getting to Mirror Lake—for me, at least—would require hitting the trail at first light.

Next, I did some virtual exploring of the Spanish Peaks on Google Earth, with the idea of finding a photogenic spot during the early dawn or pre-sunset hours. The ridge I had visited in 2008 is a good spot for a dawn photo, depending of course on how the sky looks in the morning; but the only practical way to hike from Hidden Lake at dawn is to camp there overnight. Some local folks do camp and fish at Hidden Lakes...but lacking a camping partner, I decided instead to do an evening hike at a different location.

Once again, I opted to explore a high elevation ridge with a good view across the canyon toward the peaks. The ridge I chose can be accessed by the Cherry Creeks Trail from the Spanish Creek trailhead. The trail starts just north of the parking lot, and heads north, away from the mountains, for the first half-mile. It leads far enough north that—once again—one can see the “private property” signs, instructing hikers sternly to keep to the trail. After that, there is a switchback and the route turns south, then west.

The view north of the Spanish Peaks is great!

Since the trail crosses the ridge I wanted to explore, it gains elevation fairly quickly; about 800 feet in the first mile, and then it descends on the other side of the ridge in a southwesterly direction. But since I wanted to keep to the high side of the ridge, I left the trail just before the descent and began bushwhacking my way south along the top of the ridge. Fortunately, it’s an easy bushwhack; as long as one keeps to the west side of the forested portion of the ridge, the only bushes to whack are sparse patches of sagebrush, and even those patches dwindle as the ridge gradually rises, gaining 300 feet of elevation in a little over a mile.

The sun was beginning to set by the time I reached 7300 feet. I decided I was as close to my target as I was going to get, and set up my camera and tripod to capture a series of sunset images of the Spanish Peaks, one of which is shown here.

The open subalpine meadow I ended up in was in its peak wildflower season, mainly the alpine golden buckwheat pictured here. Since I’m a sucker for wildflowers, I kept taking pictures till the last rays of sunlight faded from the peaks around me.

After the adrenaline rush of capturing images began to fade, I quickly realized I hadn’t made adequate preparations for night hiking. I should, at the very least, have brought a LED headlamp with me; a canister of bear spray and a hoodie should have been in my backpack as well.

I looked at my map and considered my options. I could have returned the way I had come, but knew the trail would be shrouded in darkness under tree cover, by the time I found it again. I glanced down at the fairly steep east slope of the ridge. It looked to be a formidable scramble—dropping a thousand feet in a third of a mile—but I knew that the Spanish Creek trail at the bottom would be easy to find, if there was any light remaining at all. So down I went, keeping to the trees for safety’s sake (If I lose my footing, young tree limbs come in very handy). Bushwhacking this route was more challenging than my earlier trek. Gravity was on my side now, but I had to contend with large rocks, fallen logs, and (of course) bushes. My “plan B” worked out, fortunately, and I found the Spanish Creeks Trail where I expected it to be. Darkness was falling fast by this time, so I covered the remaining distance to the parking lot as fast as my tired legs would go. All told, the scramble to my SUV was one mile—under half the distance I’d covered on the way up—and I was grateful for that. As it was, there was barely enough light for me to pick out my car from the other vehicles parked along the road!

That evening’s scramble was less pleasant than stressful. That lesson was not lost on me. The next time I planned a sunset hike in the Custer Gallatin National Forest, I made sure to bring an LED headlamp. I also chose a trail where mountain biking is allowed; having a bike with me made the next return trip a breeze. I’m happy to report that after the evening I spent above Spanish Creek, I haven’t put myself at risk due to lack of foresight (not very much risk, at least). I’m just as eager to capture a beautiful image as I’ve ever been, but I cannot forget the wise words of “Dirty Harry” Callahan: “A man’s got to know his limitations”.

↑ RETURN TO MAIN MENU AT TOP OF PAGE ↑

In 2015, I was fortunate enough to have lived near Colorado’s Front Range. Although it was great to live within driving distance of the Colorado Rockies and their amazing scenery, I think I was even luckier to have lived in the Montana Rockies in 2009 and 2010.

Near the Truman Gulch trailhead

In Montana, the western slope of the Bridger Range was nearly in the back yard of the place I was renting; it only took 15 minutes to drive to the nearest Forest Service trailhead. That’s an experience I have never taken for granted, having seen that real estate in the mountains is just as coveted as beachfront property in Florida.

In the course of my journeys, I’ve discovered that every place is beautiful, and every place is perfect. It’s good for me to remember this, even if I still prefer the mountains. It would be great if I owned a parcel of land in the most sought-after areas of mountain real estate. But at present, I’m grateful to have seen so much of this great country of ours, and I’ve been privileged to share my experiences with many people via the Internet. For some of you, perhaps, the Web provides the only available opportunity to explore the paths I have walked.

There are things one can experience alone to appreciate—such as looking upward on a clear Rocky Mountain night, when there are so many stars in the sky that one can see nearby rocks and trees by the starlight alone. But for me, the larger share of my joy follows naturally from sharing the experience—either on the scene, with a loved one—or later, on these pages.

In that spirit—to return to the theme of the Bridger Mountains—I am sharing a few of the things I saw during many evening hikes to Truman Gulch, as well as trips I made along Gallatin County roads and Forest Service access roads.

The open space west of the Truman Gulch trailhead is mainly hay fields and cattle ranches, but there is also a large, hilly open meadow just inside the National Forest boundary. This meadow abounds in wildflowers until late summer, and the thick patches of red paintbrush are the first thing to catch one’s eye from the access road. One evening, when the paintbrush was in “peak season”, I hiked up and down the meadow, shooting the colorful flowers from every angle. The image I considered to be the “keeper” is the one above, where the setting sun backlights the foliage—almost like a field of miniature poinsettias.

Although the Truman Gulch trail lies but a few miles south of Ross Peak, the view to the peak is blocked by a long ridge which rises about 800 feet on the north side of the trail. One weekend, I decided to follow a steep, lightly-used side trail leading northward to the top of the ridge, just to see how the scenery compared to the lower elevations. As I climbed, the trail eventually disappeared, but by that time the trees had thinned out, and the top of the ridge was in clear sight. As I approached the top of the ridge from the south, a young wolf, about the size of a German shepherd, approached the same spot from the north. We ended up surprising one another at the top. By the time I thought to reach for my camera, the wolf darted away and ran back down the other side of the ridge. I could hear it running long after it disappeared beneath the trees; it was a quiet morning in the forest, and the ground was covered with dry twigs and pine needles.

Rainbow at Ross Peak

For a while, I was disappointed about the missed photo op. It’s rare to have a one-on-one encounter with a wolf so far north of Yellowstone National Park. But I did get a consolation prize for the effort I put into climbing the ridge; I soon spotted a double-winged grass skipper visiting a patch of colorful mountain asters, and managed to get a couple of good high-magnification shots before the grass skipper flitted away.

Later in the summer, I drove toward the Bridgers, intending to hike, and found a storm cell rolling over the Bridger Range... so I ended up chasing rainbows instead. The one I pursued the hardest was beyond the end of Springhill Community Road. Realizing the futility of getting myself to the end of the rainbow for a closeup shot, I parked my car a couple of miles away from Ross Peak, aimed my telephoto zoom toward the mountain, and managed to squeeze off a few good shots.

I eventually found that the Bridgers, despite their closeness to Bozeman and Interstate 90, have an abundance of wildlife. One good example is the fawn pictured here, which I found grazing near Springhill Community Road.

I often saw deer and elk after an evening’s hike, as they sauntered down from the cover of the Custer Gallatin National Forest to feast in hayfields surrounding the foothills. During one hike, early in the springtime, I spotted a black bear uphill from me, a couple of hundred yards away. I quickly decided to retrace my steps and cut that afternoon’s hike short! Fortunately, black bears are less aggressive than grizzlies, and this one lost interest in me once I was out of sight. At least, I think so...

↑ RETURN TO MAIN MENU AT TOP OF PAGE ↑

Before I lived in southern Montana, the Gallatin Range, the Gallatin River canyon, and Hyalite Canyon were among my favorite travel destinations. Hyalite Canyon, for example, rivals Glacier National Park in waterfalls per square mile. Over time, as as the population of Bozeman and Gallatin County continues to expand, these scenic areas have become more crowded, especially on summer weekends. Folks like myself have gradually chosen less easily traveled—but more peaceful—places for day trips and weekend outings, such as the smaller Bridger and Bangtail ranges northeast of Bozeman. During the time I was fortunate enough to live in Montana, the Bridger Mountains became my favored getaway place.

The east slopes of the Bridger Mountains, which roughly parallel Montana Hwy. 86 northeast of Bozeman, are very scenic and quiet—more so as one gets closer to the peaks of the Bridger Ridge which lies west of Hwy. 86. Therein lies the challenge: Flathead Pass Road is only a “road” till one gets about a mile from the pass; the pass itself is only navigable by ATV or a skilled Jeep driver. Ross Pass is merely a trail; the Forest Service access road ends a couple of miles short of the ridge. Hikers wishing to cross the Bridgers via Ross Pass can expect a strenuous day of hiking, but the views along the way are excellent.

Fairy Lake Road, on the other hand, leads travelers directly to the base of Hardscrabble and Sacagawea Peaks, where Fairy Lake and the Forest Service’s Fairy Lake campground are conveniently located. The “saddle” between the two peaks is readily accessed from the campground by a steep but short hiking trail. The access road also leads to the easiest hiking route to Frazier Lake.

To get to Fairy Lake Road—assuming you are traveling north from Interstate 90—follow MT 86 20.5 miles north over Battle Ridge Pass. The exit for Fairy Lake Road 74 is on the west side of the highway, 0.8 miles past mile marker 21. The gravel road gives way to dirt and rock after the first couple of miles, but is fine for an SUV if driven with care.

An amazing wildflower garden covers the slopes on the way up

Close to the 7 mile point, the road curves around a pond called Elf Lake, at the foot of nearby Hardscrabble Peak, and ends at the Fairy Lake campground. If you’re looking for a quiet place to camp, you’ll probably find it here. From the campground, a short downhill walk leads to the clear waters of Fairy Lake. This lake is on the small side and has no boat access, but it is stocked with Yellowstone cutthroat trout. Few lakes in Montana that are accessible by road offer such a combination of beautiful scenery in a peaceful, quiet setting.

Frazier Lake is another midsummer treat for visitors to Hardscrabble Peak. It is a small, high lake (8100' elevation). Due to the eroded and fractured rock beneath the lake, it drains out through a subterranean channel soon after the previous winter’s snowpack melts away. If you want to see the lake, my recommendation is to time your hike for late June or early July. Aside from that, the view along this route is top-notch during the summer, when wildflowers cover the slopes along the route.

Frazier Lake, as viewed from the ridge to the south

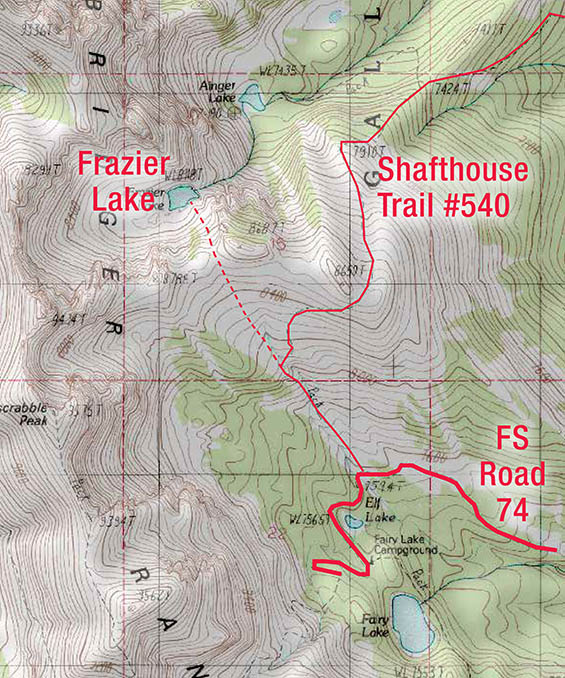

The most popular route to Frazier Lake is near Shafthouse Trail #540, which begins at the Fairy Lake Road, about a mile short of the campground. If you drive slowly, you will have no trouble seeing the Shafthouse Trail sign on the north side of the road.

From the Shafthouse trailhead sign, one can see the “saddle” that overlooks Frazier Lake, about 1¼ miles northwest of the trailhead. The Shafthouse Trail leads hikers north, away from the saddle—so to reach the saddle, one must go off-trail and pick a route through the meadow, starting at a line of bushes just behind (west of) the sign. The general route is marked by the dashed red line on the shown above. The gentle slope and decent soil conditions make for an easy hike.

If you choose a route straight up the middle of the meadow and keep your eyes on the saddle above, you will have no trouble finding your way to the top; it’s in plain view most of the way. After the first half mile, you will have a fine view of Sacagawea and Hardscrabble Peaks, and Fairy Lake will seem to be a small blue pond in the distance.

Moonrise at Fairy Lake

At the saddle itself, the views just keep getting better. Looking down the north side, you will see Frazier Lake, provided there is still enough snowpack to keep it fed. Reaching the lake is a fairly easy scramble down the slope from the ridge of the saddle. A hiking stick is helpful here, since the soil is loose and rocky.

Lupines and arnica cover the slopes northeast of Sacagawea Peak and Hardscrabble Peak — Click / tap image to view full size

In the early summer, one will find the shoreline of Frazier Lake carpeted with lupines and other wildflowers. If you choose to hike on a weekday, chances are fifty-fifty you’ll have the lake to yourself; even on weekends, the place is never crowded. Frazier Lake drains out through a gushing spring—the source of Frazier Creek, which splashes down a steep rocky slope to Ainger Lake. Those who return to the Shafthouse trail can get a view of Ainger Lake. The waterfall on the east side of Frazier Lake can be heard from the trail on a quiet day, but not seen. The spring and the waterfall can be accessed by those with moderate rock climbing skills; the location is a bit too technical for casual hikers. On the plus side, Frazier Creek and Ainger Lake offer additional opportunities for summer hikers.

On one of my hikes up to the ridge, I found a place where I could wedge myself into a narrow draw and take a series of vertical pictures that I later combined into a wide-angle view. The rocky draw wasn’t cushy or comfortable, but I liked my vantage point because it exaggerated the perspective of the many wildflowers along the sunny slopes, and because it had a great west view toward Sacagawea Peak and Hardscrabble Peak. The wide-angle view I saw is displayed here.

If you find yourself in the Montana Rockies in midsummer, I hope you find many scenic panoramas of your own!

↑ RETURN TO MAIN MENU AT TOP OF PAGE ↑

During the winter holidays, many of us associate the season with images of bundling up with the kids, playing outside in the snow, then coming back inside with ruddy faces, shedding our very wet outerwear, and drinking hot chocolate.

I have spent the last dozen winters in Florida, whose residents miss out on all that fun stuff. Fortunately, before moving south I spent some time living in the Rocky Mountains. Mountain winter seasons can be unpredictable and cold—but not cold enough to keep away the skiers and snowboarders that flock to the ski slopes every year!

I discovered the snow and icicles pictured here close to one of those ski areas, in the Custer Gallatin National Forest. That spot happens to be a place where families come (usually with permits in hand), to choose the perfect Christmas tree to cut and take home with them.

During this visit to the National Forest, I noticed that this living Christmas tree was decorated with real icicles, which sparkled in the sunlight. No Christmas lights I’ve seen are more splendid than these!

The higher altitudes are generally better for finding great winter scenery, but the lowlands often reveal nice winter vistas. For instance, if you find open water on a very cold morning at sunrise, there is a good chance you’ll see a photogenic layer of fog over the water, which provides all sorts of photo opportunities. Where there has been heavy morning fog, there is often frost.

One morning early in December 2009, I drove from my house just north of Bozeman west to Big Timber via Interstate 90. I had spent time exploring the Boulder River the previous summer, and hoped for a good photo op somewhere in the National Forest lands south of Big Timber.

The Boulder River access road is Montana Hwy. 298, which follows the river roughly southward from Big Timber. On this particular day, I decided to go beyond the main Boulder valley and explore the East Boulder Road, which crosses the Boulder River and follows one of its tributaries, the East Boulder River, up into the Beartooth Mountains.

I did a lot of driving that day over snowy backroads, and got plenty of exercise taking short hikes from my SUV through deep powdery snow. But midday sunlight is generally not good for capturing scenic landscapes—and to be honest, I didn’t find great winter scenery at that location to begin with. The road I was driving was freshly plowed and graded, which was a nice surprise... so I figured I would follow it past the empty East Boulder USFS campground as far west as I could.

That turned out to be a shorter trip than I expected: A small private mining operation, not shown on my maps, blocked the road with a chain-link fence and a steel gate. I had little choice but to turn around and head back down the East Boulder canyon. The road had obviously been plowed for the benefit of the mining traffic. I was disappointed that my trip was cut short... and the setting sun was now in my eyes, so I was obliged to flip my sunshade down and squint through my windshield.

Hoarfrost near a spring at Wright Gulch in the Beartooth Mountains

Then, as I rounded a bend in the road and came in view of Wright Gulch, I was amazed to find something I had barely paid attention to earlier: A tiny, spring-fed creek which coursed down the gulch to join the East Boulder River. Everything within a dozen yards of the creek was covered in thick, crystalline hoarfrost—which was beautifully backlit by the same evening sunlight that had annoyed me while I was driving.

I quickly parked my car, grabbed my camera gear, and hiked up to the “frosty zone”. It appeared that the clear spring water, despite being very cold, had been warm enough to fog up the air on the previous night... and everything the fog touched was now covered with sparkling ice crystals.

So—as often happens—I’d spent an entire day driving to and fro, only to capture my “keeper” images at day’s end. You’ll notice that in the picture of the sun shining through the trees, the sun was barely above the ridgeline in the background.

Capturing the photos was the easy part. The tough part was trying not to mess up the snow anywhere within view of my camera. I figured that a line of boot-prints marching through the foreground of these images would be... well, a distraction.

My boots and jeans, which got soaked while tramping through the snow, were nearly frozen by the time I returned to my SUV. Despite that, I felt warm and content inside while driving toward Big Timber through the darkening canyon. It had been a good day.

In the Rockies, places such as hot springs and waterfalls are often as photogenic in the winter as they are in the summer. The smaller waterfalls freeze solid, while the larger ones continue flowing, hidden from view by a thick shell of icicles.

I had previously explored the winter wonderland in Hyalite Canyon, south of Bozeman, on more than one occasion. To put it as simply as possible, Hyalite features many waterfalls, and its geography makes the upper canyon a popular destination for ice climbers. The Bozeman Ice Festival takes place there annually, early in December.

Ice climbing isn’t for everyone—even those skilled at rock climbing—for obvious reasons. Ice is more brittle and unpredictable than rock. Most climbers take all possible precautions, but no one can predict when a chunk of snowpack might come loose from above and sweep a climber to the bottom of the canyon. Near-death experiences aren’t rare. There are plenty of video clips on YouTube to prove the point.

Happily most of us don’t live our lives so “close to the edge”. If you enjoy photography, hot drinks, and winter hiking as much as I do, the annual Bozeman Ice Festival is rather fun, and not very dangerous.

In January, about a month after exploring the East Boulder valley, I took a day trip from Bozeman up to the Little Belt Mountains in the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest, by way of US Hwy. 89. As I approached the forest boundary from the south, I noticed that the side roads were popular with local snowmobilers. Within the forest boundary, there are also lots of non-motorized winter activities.

My destination was Memorial Falls Trail 738, which is close to Hwy. 89 and not far from the town of Neihart and Showdown Montana, a small ski area. The Forest Service recommends using the Memorial Falls trail through mid-autumn, but it’s a short trail with a low level of difficulty. Sensible winter hikers, who strap ice cleats onto their boots and use hiking poles, will have no trouble (as long as they stay out of the creek!).

Memorial Falls is not the only waterfall on Trail 738, but it is the largest one, and the one closest to the trailhead. Though I had to pay close attention to where I placed my feet, I had fun poking around the falls, trying to find a good shooting angle. The top of the photo shown here gives the impression that Belt Creek was completely frozen, but in the bottom of the picture, one can see some water trickling over the rocks. As was the case in Wright Gulch, the temperature of the creek bed at this spot stays just above freezing, even when the air temperature plunges toward zero during Montana’s cold winter nights.

My kids grew up long ago, so I’m able to take solo trips to out-of-the-way places in hopes of finding a nice bit of scenery. I realize that most of my readers don’t have that kind of time on their hands, so this blog entry is not so much a travel guide; it’s just an example of what you can find if you plan to travel to a winter resort destination. The Internet is a wonderful thing; I often use it to search for interesting places near my actual destination prior to leaving for a trip. Sometimes, I have a window of time to take a side trip and check out those interesting places. Often, there isn’t much to see... but just as often, I am pleasantly surprised by what I find.

On that note, I wish all my readers many pleasant surprises during their travels!